Will blueberries continue to turn the tundra blue?

A text by Valérie Levée, science journalist

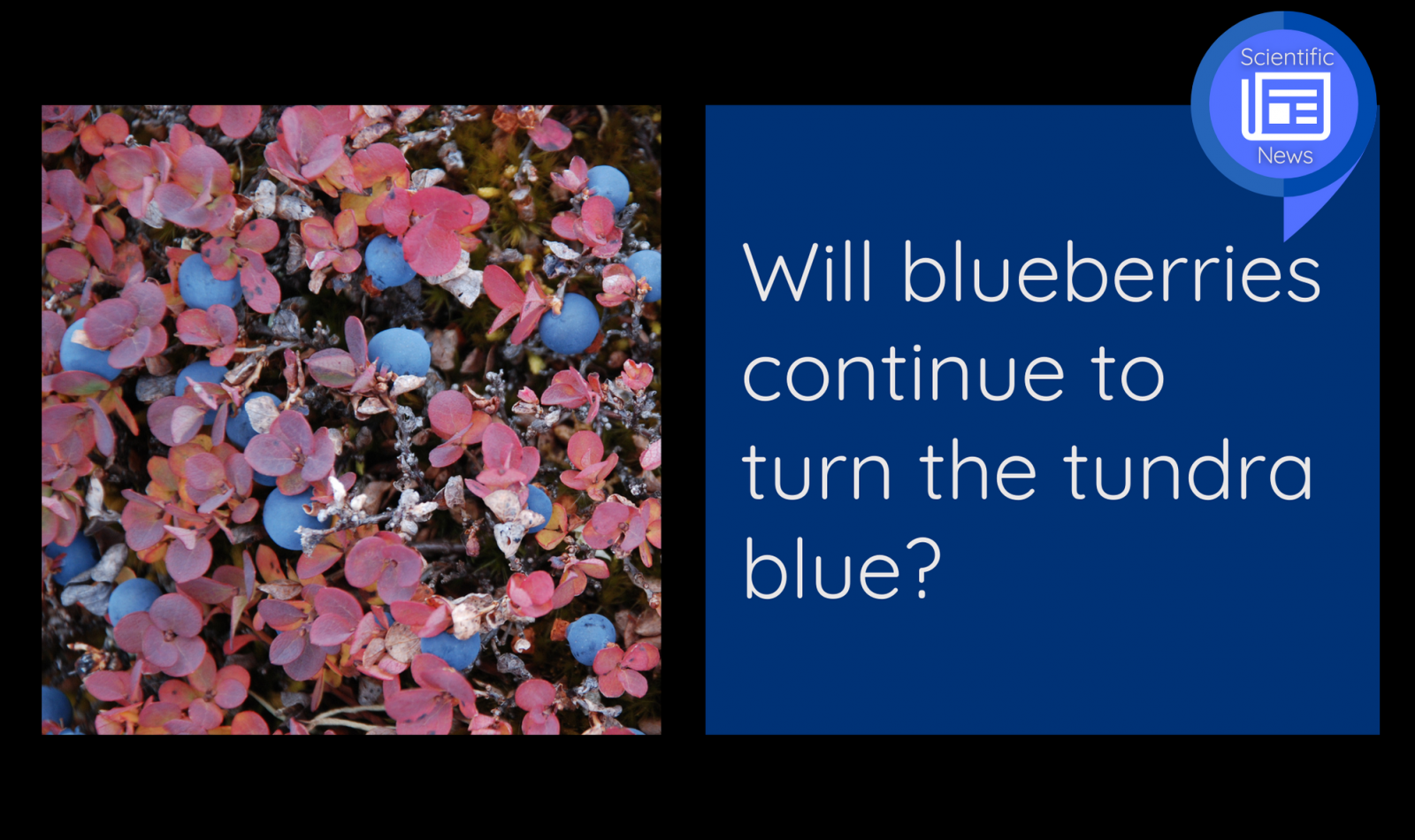

As elsewhere, Arctic vegetation is undergoing climate change. But if the Arctic turns green, will the blueberries still turn blue? The question is not trivial for the Inuit, for whom blueberries and other berries represent an important nutritional source and contribute to community wellbeing on the land.

Esther Lévesque is a professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences at UQTR and is co-director of INQ’s axis 3 on Ecosystem functioning and environmental protection. She is interested in vegetation changes in the Arctic. Along with her research team and northern communities, she has focused part of her research on berries, combining field measurements with surveys in Inuit populations.

As aerial photographs and satellite images show, the Arctic is greening up. It's not the tree line that's moving north, but the shrubs that are expanding, particularly dwarf birch. "In the field, samples were taken to see when the shrubs started to grow and we can see that it is in the last 20 years that they have increased in height," explains Esther Lévesque. While some individuals have remained low to the ground for many years, in some places they have grown by tens of centimetres to reach 1.50 metres and sometimes more. The dwarf birch will nevertheless not become a tall tree and will remain a shrub, but its expansion could harm the smaller flora, particularly small-fruited species such as blueberries, crowberries and cranberries.

What the Inuit are saying

The people best placed to observe changes in vegetation are the Inuit, who are accustomed to picking berries at the end of the summer. "They travel with their families to camp or hunt and pick berries around their campsites," says Esther Lévesque. The women make suvalik, a kind of mayonnaise traditionally made from berries, seal fat and fish eggs. Berries are a seasonal but sought-after source of food that is traded and even sold. "There is a lot of trading in the communities. People who work and can't go and pick berries are looking to buy them. On Facebook, we see ads and recipes for suvalik," says José Gérin-Lajoie, a research professional who has coordinated several projects in northern communities. In particular, she conducted surveys in 7 communities with local experts to find out their perception of climate change, changes in vegetation and knowledge related to berries. "Previously, studies about traditional knowledge were primarily surveys of hunters and therefore mostly men. In this project, we were dealing with a more traditionally female theme," observes José Gérin-Lajoie. Their answers show that the weather is more unpredictable, ice sets later and thaws faster, vegetation is changing, shrubs are growing taller, some berry sites are becoming less productive and others more productive, and that access to harvesting sites will become more difficult. "People complain that there are bushes in the way or that the water level in the river has dropped and it is no longer possible to reach a berry picking site by boat," reports Esther Lévesque. But "these resources are so precious to them that they will adapt, modifying their movements to access this resource," adds José Gérin-Lajoie.

Productivity on the land

To complement this data, the team wanted to measure berry productivity in the field. A protocol for collecting, counting and weighing berries per unit area was established and implemented in various Arctic communities by both university and Nunavik high school students through the Avativut educational project developed in collaboration with the Kativik Ilisarniliriniq School Board.

Above all, the measurements compiled in a database showed a great variability in production from one site to another, between regions and over the years. Climate change affects the phenology of pollinating insects and flowers, so multiple factors affect plant productivity. "If the weather is bad during the short pollination window, the insects don't emerge and there is no production," says José Gérin-Lajoie. "The only clear conclusion is that there is shrub competition.

If erect shrubs become established, berry productivity will definitely decrease," adds Esther Lévesque. Isabelle Lussier studied this issue for her thesis project by measuring the productivity of blueberry, crowberry and cranberry plants under and alongside shrubs as well as those outside a shrub zone. "Blueberry and crowberry are productive in open areas. Under shrubs, the plants are present and continue to grow but they produce less fruit. Cranberries seem to benefit a little from the protection of shrubs, but they are not very productive, so the gain is not great," says Esther Lévesque.

View from above

Field data give only a very fragmented view of vegetation transformation and berry productivity. To get a landscape-level view, we need to get up high and develop remote sensing tools that would allow us to distinguish the composition of the vegetation. "At the moment, remote sensing measurements indicate that the Arctic is greening, but we don't know whether the greening is limited to upright shrubs like birch or whether it includes other plants. We are trying to develop specific indices for berry species," explains Esther Lévesque. For example, at the end of the summer, the leaves of blueberry plants turn red while birch trees turn yellow.

The tundra is certainly changing, but to the delight of the Inuit, there will always be berries.

Information about the researchers

1 - Esther Lévesque is a professor in the Department of Environmental Sciences at UQTR and is co-director of INQ’s axis 3 on Ecosystem functioning and environmental protection.

2 - José Gérin-Lajoie is a research professional in the Department of Environmental Sciences at UQTR.

Further reading

Boulanger-Lapointe, Noémie, Greg H.R. Henry, Esther Lévesque, Alain Cuerrier, Sarah Desrosiers, José Gérin-Lajoie, Luise Hermanutz and Laura Siegwart Collier (2020) « Climate and environmental drivers of berry productivity from forest-tundra ecotone to the High Arctic in Canada »,

Arctic Science, 6 (4), 529-544. https://doi.org/10.1139/AS-2019-0018

Boulanger-Lapointe, Noémie, José. Gérin-Lajoie, Laura Siegwart Collier, Sarah Desrosiers, Carmen Spiech, Greg H.R. Henry, Luise Hermanutz, Esther Lévesque and Alain Cuerrier (2019) « Berry plants and berry picking in Inuit Nunangat: traditions in a changing socio-ecological landscape », Human Ecology, 47(1), 81-93. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10745-018-0044-5

Gérin-Lajoie, José, Alain Cuerrier and Laura Siegwart-Collier Ed. (2016) The caribou taste different now: Inuit Elders Observe Climate Change. Nunavut Arctic College Media. 314 pages. ISBN 978-1-897568-39-2

Tremblay, Benoît, Esther Lévesque and Stéphane Boudreau (2012) « Recent expansion of erect shrubs in the Low Arctic: evidence from Eastern Nunavik », Environmental Research Letters, 7(3) 035501. https://doi.org/10.1088/1748-9326/7/3/035501

Science News

Science News

Spotlight on Northern Research | An initiative of Institut nordique du Québec

To celebrate Quebec's excellence in northern research and to highlight the various challenges and issues related to these territories, Institut nordique du Québec offers you a series of articles dedicated to the research conducted in its community.

Over the months, you will discover a multidisciplinary research community whose strength lies in the complementary expertise of its members. You will meet individuals who share a strong attachment to the North and who are dedicated to producing, in collaboration with the inhabitants of the region, the knowledge necessary for its sustainable and harmonious development.

You are invited to relay this and subsequent articles to your network, thus enabling the greatest number of people to discover the different facets of northern research and the many faces that animate it. Together for the North